History of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

-

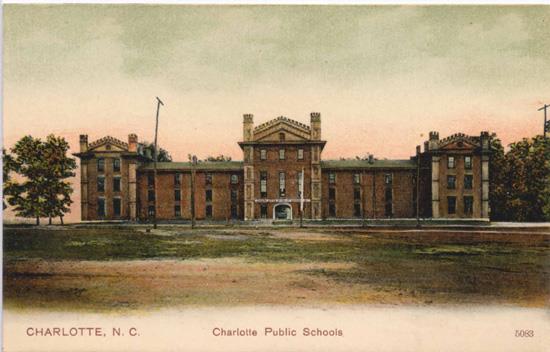

The Early Years 1882-1935

Today, the public school district known as Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools began in Charlotte in 1882 when T.J. Mitchell was chosen as the first superintendent of the segregated city school district. The system's first school, known as the South School, was located on the corner of East Morehead Street and South Boulevard in the barracks of the Carolina Military Institute. The first school for African-American children was organized in 1882 and was known as Myers Street School.

From 1886 to 1888, Professor J.T. Corlew, a former school principal in Charlotte, served as the second superintendent of the city school system.

From 1888 until 1913, Dr. Alexander Graham served as superintendent of what had become known as the "largest public school system south of Baltimore." Often called the father of graded schools in North Carolina, Graham developed a co-ed school, dropped Latin and Greek, and added drawing and music to the curriculum. He opened the district's second school for white students in 1900, the North School, which served students to the 10th grade. The school's layout, which was described as the finest school building in North Carolina, was developed from plans for a hospital in Texas. Today, First Ward Accelerated Learning Academy stands on the site of the North School.

From 1888 until 1913, Dr. Alexander Graham served as superintendent of what had become known as the "largest public school system south of Baltimore." Often called the father of graded schools in North Carolina, Graham developed a co-ed school, dropped Latin and Greek, and added drawing and music to the curriculum. He opened the district's second school for white students in 1900, the North School, which served students to the 10th grade. The school's layout, which was described as the finest school building in North Carolina, was developed from plans for a hospital in Texas. Today, First Ward Accelerated Learning Academy stands on the site of the North School.The district expanded in 1907, pulling several county schools into the city district. Some of the schools included Dilworth School, Seversville School, Elizabeth Mill School, Belmont School, and Biddleville School.

Dr. Harry Harding was named superintendent in 1913, and school construction continued during the next decade. In 1920, Alexander Graham High School was built, and three years later, Central High School was established. The Alexander Graham School became the state's first junior high school. In 1925, a 12th grade was added to the graded school system.

During the Depression, the school district experienced great difficulty with a budget cut of 61 percent and elimination of the 12th grade in 1934 and the elimination of teaching and other positions. Many positions were also cut during this time. In 1935, 12th grade was reinstituted.

-

Consolidation 1935 -1953

The county school system, which had previously been led primarily by committees that gave schools a lot of autonomy, began to change. In the mid-1800s, more than 80 schools in the county enrolled more than 3,500 students. After the turn of the century, one-room and two-room schools were consolidated.

From 1944 to 1960, J.W. Wilson served as superintendent of the county school system. He consolidated many of the schools in the county system. Under his supervision, East, West, North and South high schools were established.

In 1949, Dr. Elmer Garinger was chosen as superintendent of the city schools. In that same year, the Institute of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill recommended consolidating the Charlotte City Schools and Mecklenburg County. The institute said that consolidation would result in several advantages, most notably equal educational opportunities for all children.

The Charlotte Chamber of Commerce recommended a study committee examine extending the city limits and consolidating the two school systems. Under the leadership of Richard Thigpen, the study committee and the Chamber of Commerce concluded that the best solution for local school problems would be to consolidate. A well-known civic leader, Oliver Rowe, was instrumental in getting the public to vote for the consolidation, making numerous presentations and speeches throughout the county.

On January 13, 1958, the Chamber committee's final report requested that the city and county boards of education pursue enactment of appropriate legislation by the 1959 General Assembly that would make consolidation possible.

On June 30, 1959, residents of Charlotte and Mecklenburg Counties voted by a 2-1 margin to consolidate the two school systems. The voters also approved levying a 50-cent school tax to serve the children of Charlotte-Mecklenburg. As a result, on July 1, 1960, the Charlotte City Schools and Mecklenburg County Schools were merged, joining the two largest school districts to form a new city-county school district.

Dr. Elmer Garinger, the superintendent of the city schools, was appointed superintendent of the new consolidated system. J.W. Wilson (the county superintendent) was appointed deputy superintendent by the consolidated Board of Education chaired by Dr. Herbert Spaugh.

One year later, Dr. Garinger announced his retirement and a search committee was formed to find his successor. Dr. A. Craig Phillips, superintendent in Winston-Salem, was named the new superintendent for Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. Under his leadership, the district developed a uniform curriculum program and personnel policies.

A major issue addressed by consolidation was the adoption of a reading program. The city school system had used a conventional phonics program while the county had created its reading program. As a result, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools decided to develop a comprehensive reading program for the merged system

-

Desegregation 1954 - 1975

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that the "separate but equal" doctrine, which had been in effect since 1896, was unconstitutional. The high court also declared that separate schools were "inherently unequal" and that schools must desegregate with "all deliberate speed."

At the time, Charlotte was very much a segregated city, with black schools and white schools within the district. The schools reflected the larger social context in a city with no integrated hotels, restaurants, restrooms, churches, cemeteries or theaters.

At the time, Charlotte was very much a segregated city, with black schools and white schools within the district. The schools reflected the larger social context in a city with no integrated hotels, restaurants, restrooms, churches, cemeteries or theaters.For three years following the Brown decision, there was no move to comply with the law. There was no real pressure from the community, and the prevailing attitude was to wait and see. Then, in 1957, black citizens moved to take advantage of their legal right to attend white schools.

Four black students entered white schools in 1957. Delores Huntley attended Alexander Graham Junior High School for one year. Girvaud Roberts attended Piedmont Junior High School for two years. Gus Roberts graduated from Central High School in 1959. Across town at Harding High School, now the location of Irwin Avenue Elementary, the school's first black student, Dorothy Counts, attempted to enroll. Still, her entrance into school stirred an angry response. A photo taken on the first day of school shows her surrounded by an angry, jeering mob. The picture appeared in many newspapers across the Southeast. However, Charlotte received national attention for desegregating schools with relative ease. Gus Roberts' graduation from the formerly all-white Central High School was not achieved without some resistance. But Principal Ed Sanders and other staff supported him and worked hard to keep order within the school. Counts, however, ended up finishing her secondary education in another state. (She returned to Charlotte to live, however.)

Like many others across the country, the new district struggled with desegregation. However, great disparities between schools had not ended with consolidation. Instead, a pattern of massive "white flight" emerged, with families moving to the developing suburban areas of the county as a means of avoiding desegregation.

Ten years after the Brown decision, segregation was still the reality in Charlotte-Mecklenburg. In 1964, the system had 88 segregated schools – 57 white and 31 black. This led to one of the most significant court cases in the region's history in 1965: Swann vs. the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education.

The case was brought by the Rev. Darius Swann and his wife, Vera. They had been missionaries in India and had returned to Charlotte. The Swanns' son, James, had attended integrated schools in India, and his family strongly valued the experience. The school closest to the Swanns' home in Charlotte was Seversville, a school with 297 white students and 26 black students. After James' first day at Seversville, he was told that he was at the wrong school and should be assigned to Biddleville, an all-black school. The Swanns contended that children could "transfer out of integrated schools, but not allowed to transfer into them and that the law should be equally binding…otherwise, the law is discriminatory."

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education denied the Swanns' request that James attends Seversville. On January 19, 1965, Charlotte attorney Julius Chambers filed suit on behalf of the Swann family and nine other families. The suit took many years to resolve (the Swanns left the area two years later, but the suit played on). The suit alleged:

Some dual school zones remained in operation, creating essentially black and white school districts side by side,

Compounding the problem, the Board of Education permitted transfers out of integrated schools but discouraged transfers into the schools,

Most school faculties were completely segregated.

On July 12, 1965, Judge Braxton Craven ruled in favor of the Board of Education, saying it had shown clear intent and had made steady progress toward ending a policy of segregated schools. Only 2,126 of the district's 23,000 black students attended school with white students, and 66 of Charlotte's 109 schools were entirely segregated. Craven's ruling also ordered immediate desegregation of staff and faculty.

Chambers appealed the decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld Craven's ruling on October 24, 1966. However, the case was revived two years later when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a Virginia case that Kent County had an obligation to eliminate historic patterns of segregation. The county had a black high school and a white high school, and the court found that freedom of choice was not an adequate remedy. Chambers saw this decision as an opportunity to reopen the Swann case because the decisions of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education did not meet the standards set by the Supreme Court in the Kent County (Virginia) case.

Chambers appealed the decision to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which upheld Craven's ruling on October 24, 1966. However, the case was revived two years later when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a Virginia case that Kent County had an obligation to eliminate historic patterns of segregation. The county had a black high school and a white high school, and the court found that freedom of choice was not an adequate remedy. Chambers saw this decision as an opportunity to reopen the Swann case because the decisions of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education did not meet the standards set by the Supreme Court in the Kent County (Virginia) case.Chambers refiled the Swann suit in March of 1969. On April 23 of that year, federal Judge James B. McMillan ruled that the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools district was not desegregated. McMillan noted that "approximately 14,000 of the 24,000 black students still attended schools that were all black or heavily black, and most of the system's 24,000 teachers were white."

McMillan directed the Board of Education to submit a positive plan to desegregate the schools by the fall of 1970. He specified that "the Board is free to consider all known ways of desegregation, including busing."

The Board developed several plans. McMillan rejected all, who then appointed Dr. John Finger of Rhode Island to prepare a plan for total integration. The Finger plan was submitted, and McMillan ordered the Charlotte district to put it in place. But the Board of Education appealed the order. The Fourth Circuit Court directed McMillan to hold new hearings and apply the "test of reasonableness" to the extensive busing of elementary students. McMillan held the hearings, and in August 1970, he reinstated his February decision, effective with the opening of schools. Again, the Board of Education appealed, and the Supreme Court affirmed the McMillan order. School opened on September 9, and the district had 525 buses in service, 191 more than a year earlier, to transport students.

Dr. Phillips resigned on June 30, 1967, and Dr. William Self was named superintendent.

Work continued on the desegregation plan, and the Board of Education approved a busing plan in July 1974 that McMillan approved. Finally, in 1975, McMillan was satisfied that the plan was indeed working, and he closed the Swann case nine years after it was first filed.

-

Moving forward 1972 - 1996

Dr. Self resigned in 1972. Dr. Roland Jones was hired as superintendent in 1973 and dismissed by the Board of Education three years later. In 1977, Dr. Jay Robinson was named superintendent. In 1986, Dr. Robinson was appointed to serve as the vice president of the state university system. In 1987, Dr. Peter Relic was named superintendent.

Dr. John Murphy became superintendent in 1991. He launched a new magnet school program the following year designed to match students' interests and learning styles with particular themes. Another purpose of the program was to replace the 22-year-old system of paired schools and cross-town busing to ensure desegregation. The magnet school program was developed to accept students through an application lottery process, with acceptance based on a 60:40 race quota.

In 1996, Dr. Eric Smith was named superintendent, setting four goals for 2001, which focused on academic achievement, a safe and orderly environment, community collaboration and efficient and effective support operations.

-

Swann returns 1997 - 2002

Student assignment resurfaced as a district issue in 1997 when Charlotte parent Bill Capacchione sued the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school system, charging that his daughter was twice denied entrance to a magnet school because she was not black. The Swann attorneys announced in October 1997 that they would join the case to fight the Capacchione suit, saying that the school system had not fully desegregated and should not be released from court-ordered desegregation.

In March 1998, U.S. District Judge Robert Potter reactivated the Swann case and consolidated it with Capacchione's suit. Two months later, six parents joined the case saying that race-based policies influence everything from how students are assigned to where schools are built. The parents argued that the district's schools were fully desegregated and continued use of race-based policies was unconstitutional. On the other side, several black parents joined the Swann team, seeking to keep the desegregation order.

On September 9, 1999, Judge Robert Potter ruled that the school system must stop using race as a factor in student assignment plans. In October 1999, the school board voted to appeal Judge Potter's ruling to the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, seeking a stay to delay the new student assignment plan that would not use race as a factor in student assignment. Two members of the Swann team also filed an appeal and a stay request.

In November 1999, Superintendent Eric Smith proposed a new student assignment plan to send students to schools closer to home and provide families with choice. The assignment plan was developed based on choice zones and offered K-12 stability to families. The Board of Education approved the plan after soliciting public feedback. The appeals court granted the Board's request for a delay in the Swann/Capacchione ruling.

In January 2000, the Board of Education voted to delay the new student assignment plan until fall 2001 and convene a citizens task force to make recommendations on the new student assignment plan. In May, the Board agreed to use mediators to select a plan, and one was adopted on June 1.

The new student assignment plan focused on the following areas:

- Giving families a chance to choose a school close to home.

- Preserving the integrity of choice.

- Addressing growth in a reasonable way.

- Offering stability through K-12 feeder patterns.

On June 7, 2000, the Fourth Circuit Court heard the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools desegregation case. In a ruling issued November 30, the court found that CMS was not unitary in some areas such as facilities, student assignment, student achievement, and transportation and sent them back to the lower court for reconsideration. However, faculty, staff, extracurricular activities and student discipline were considered unitary. The Board of Education voted on December 1 to set aside the new family choice plan to comply with the ruling.

The Board of Education continued to work on a desegregation plan based on the family-choice framework, ultimately approving a new student assignment plan in July 2001 that withstood legal challenges. The plan was put into place for the 2002-2003 school year.

While the Swann and related cases churned through the courts, CMS was fast gaining recognition as an urban school system making tremendous academic gains under the leadership of Dr. Eric Smith. The district gained national attention for its student achievement and participation in higher-level courses. The National College Board awarded the first Advanced Placement diplomas in the nation to CMS students. In addition, Dr. Smith received the Richard R. Green Award from the Council of the Great City Schools. This organization represents the largest urban school system in the country. The district was also recognized by the Council of the Great City Schools in 2001 as one of four top urban school districts for increasing scores in reading and math and closing the achievement gap.

On April 15, 2002, the United States Supreme Court announced that it would not revisit the Swann/Cappachione cases and related petitions, allowing the Fourth Circuit's approval of the district's student-assignment plan to stand. The decision effectively closed the Swann case.

-

Plaudits and prizes 2002 - Present Day

In May 2002, Dr. Smith announced that he had accepted an offer to become superintendent of Anne Arundel County Public Schools in Maryland. On May 28, 2002, the Board extended a two-year contract to Dr. James L. Pughsley to serve as superintendent of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. Dr. Pughsley was the deputy superintendent and the first African-American to lead the district as superintendent.

Dr. Pughsley continued the district's focus on academic success and rigor for all students. As a result, the district was recognized by the Council of the Great City Schools as one of four urban school districts making outstanding gains in student achievement while narrowing the achievement gap.

In April 2005, Dr. Pughsley announced that he would retire in June. In May 2005, the Board of Education voted to hire Dr. Frances Haithcock as interim superintendent for one year, beginning July 1. Dr. Haithcock was associate superintendent for education services in CMS for five years.

In December 2005, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools earned district-wide accreditation from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools and Council on Accreditation and School Improvement, the first large urban district in the country to do so.

Dr. Peter Gorman became CMS superintendent in July 2006. Dr. Gorman had been superintendent of Tustin Unified School District in Tustin, Calif. Dr. Gorman continued the district's focus on academic achievement. In addition, he introduced a four-year plan for the district, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools Strategic Plan 2010: Educating Students To Compete Locally, Nationally and Internationally. Based on the Theory of Action adopted by the Board of Education, the plan revised the district curriculum and put more authority at the school level, partially decentralizing CMS. He also brought in significant new partners for the district, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the C.D. Spangler Foundation, the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation and the Wallace Foundation. He strengthened the district's connection to Teach For America and Communities In Schools.

Dr. Gorman resigned in June 2011 to accept a job in private industry. The Board of Education named Hugh Hattabaugh, the district's chief operating officer, as interim superintendent for a year while a nationwide search was launched for a new leader.

In September 2011, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools won the Broad Prize for Urban Education. The prize, the largest of its kind, recognizes districts that simultaneously increase achievement and close the achievement gap. The district had been a finalist on two earlier occasions.

In May 2012, the Board of Education announced that Dr. Heath E. Morrison would assume the district's leadership in July. Dr. Morrison was superintendent in Washoe County, Nevada (Reno) and was named national superintendent of the year in 2011 by the American Association of School Administrators.

Dr. Morrison resigned in November 2014. Deputy Superintendent Ann Clark was named superintendent while the Board of Education began searching for a new leader. Clark joined the district in 1983 as a teacher of behaviorally and emotionally handicapped children at Devonshire Elementary and has served as a teacher, principal and in various administrative positions before assuming the superintendency.

The Board of Education announced in December 2016 that Dr. Clayton M. Wilcox had been selected as the new superintendent. Clark retired at the end of June 2017, and Dr. Wilcox was sworn in on July 3, 2017.

Before joining Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Dr. Wilcox had been superintendent of Washington County Public Schools in Hagerstown, Md., since 2011. Previously, he served as superintendent of schools in Pinellas County, Fla., and Louisiana's East Baton Rouge Parish School System. In addition, he worked at Scholastic Inc. as a vice president and senior vice president for education and corporate relations. Dr. Wilcox resigned in July 2019.

In August 2019, the Board of Education chose Earnest Winston as the new superintendent. A former journalist, Winston joined CMS in 2004 as an English teacher at Vance High School (now Julius L. Chambers High School). He moved into the district's communications department two years later and subsequently served in several executive leadership roles. He was chief of staff from 2011 to 2017, when Dr. Wilcox named him the district's chief community relations and engagement officer.

Winston's contract as superintendent was terminated in 2022. Dr. Hattabaugh came out of retirement to serve a second term as interim superintendent, but he left the position at the end of 2022.

Dr. Crystal Hill, chief of staff, became interim superintendent at the beginning of 2023. In July, she became the district's first Black, female permanent superintendent. Dr. Hill began her teaching career in Guilford County Schools. She served in a number of roles for Mooresville Graded School District, Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools and Cabarrus County Schools, where she was assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction before joining CMS in 2022.

In 2023, Dr. Hill led the district’s successful, historic $2.5 billion bond campaign -- the largest in state history -- and had the first fully funded county budget request in recent CMS history. In 2024, she had a fully funded budget request for the second consecutive year.